From the Cellar: Showdown! Commercial vs. Homebrewed Smoked Porter

For this edition of From the Cellar, I opened a bomber of Ranger Creek Mesquite Smoked Porter (6.4% ABV) and pitted it head-to-head against my own homebrewed porter currently on tap: Smokey in a Plain Wrapper Rauch Porter (6.0% ABV).

Smoked porter or rauch porter is one of those style variations that seems to be springing up in all sorts of places spontaneously. Granted, Stone has had their version on the market for over 15 years now, so it’s possible we all got the same great idea from them. But it is a great idea. The astringency and bite of smoked malt plays well against the sweet and malty backdrop of a porter malt bill, giving complexity without having to resort to a ton of hops in the boil. It gives a flavor akin to stout without the sharp roasted barley notes that are so common (though not necessarily required) in a stout. So yeah, I’m a fan; and I was dying to know how one of my own brews stacked up against a commercial offering from one of my favorite up-and-comers in the Central Texas craft beer scene.

I poured a blind tasting of both beers and tried them side by side. I didn’t know which was which until after I had written down all of my notes. Picking a clear winner was tough, so I just judged each on its merits and avoided trying to score them (though I did have a personal favorite).

Beer A was nearly black with chocolate brown notes, and tiny bubbles with not a lot of head retention. The nose had some slight but noticeable fruity esters over dark chocolate and coffee. The aroma of smoke was present, but not obvious.

Beer B had a much more persistent head and was completely black with bigger and rockier bubbles. There was a distinct woodsy scent and a smell not entirely unlike good Texas barbecue. But the beer had a boozy smell, like it was barrel-aged, which would be a surprise. The thick head and carbonation would suggest that if it was aged, it wasn’t aged for any considerable length of time.

As for the flavor, I generally preferred Beer A even though Beer B was arguably a better crafted brew and a better example of a rauch porter. Beer A was full of dark chocolate and vanilla flavor, with a slight amount of esters and very little smoke. But it was refreshing and easy to drink, and ultimately really satisfying. Beer B was cleaner fermented, but the smoke really, really dominated the flavor … to the point of being almost too much for me. There was some leather and wood in Beer B, but really it was all about the smoke. It was drier than Beer A, but less refreshing because of the harsh, aggressive character I found the smoke imparted.

Within seconds of tasting, I knew which one was mine. Smokey in a Plain Wrapper has been on tap in my kegerator for a couple of months, so I know it pretty well and could pretty much tell it was Beer A. The Ranger Creek Mesquite Smoked Porter was Beer B.

So while the results weren’t shocking, they were very informative. My homebrew was more estery and with less smoke flavor (thus arguably less true to the essence of a rauch porter) than a commercial equivalent. But I would rather drink my homebrew, even when I didn’t know it was my homebrew, simply because it was more refreshing. Am I just getting used to the unique flavor produced in my brewing setup, or am I just subconsciously making beers I like? Or was it simply the fact that I wasn’t crazy about the mesquite smoke in the Ranger Creek beer, and another rauch porter from another brewery (with another kind of smoke) would have fared better? It’s hard to say. It could have been just familiarity with Smokey that made me like it more.

Regardless, it’s great to know that I like my beers not only because I made them, but that they also stack up well against commercial brews. I have no idea how I’d do against the commercial brew before a panel of judges, but as long as I like it and want to drink it (and share it with others) that’s good enough for me. Prosit!

Old Faithful: The Saga of JR 11/27

I hate to jinx myself by saying it, but I’ve been pretty lucky as a brewer. Since I started brewing three years ago, I’ve been happy with almost every beer I’ve made. Even my first few all-extract batches were pleasing enough; granted, I had no idea how much better my beers could be. But I learned from every mistake and obsessed over details, and consequently, I can honestly say that almost every beer I’ve made has been better than the one before it.

Except for one.

It was November 2010, and I was partial mash brewing for nearly the last time (I switched to all-grain brewing in January 2011). The recipe was a juniper rye ale kit from Austin Homebrew Supply, and I had chosen it as my holiday beer for that year. I conducted the stovetop mini-mash with zeal, anticipating the adoring looks I’d get from family and friends as I proudly poured gleaming bronze ale into their eager glasses. I inhaled deeply as I crushed the juniper berries in a mortar and pestle, imagining what that piney, herbaceous scent would add to the aromas of Christmas dinners filling the air in the homes of my loved ones.

The brew session went spectacularly, as did fermentation. I bottled on November 27, christened the batch number JR 11/27, and poured the first taste eleven days before Christmas. It was okay – in need of some aging, but promising.

But when the holiday arrived, disaster struck. The first bottle I opened foamed over. Yes, we smelled juniper, but were distracted by the geyser of beer spilling out all over my hands and the floor. I tried another, and another, with the same results. I realized with horror that JR 11/27 was one of those beers homebrewers dread making: a “gusher”, overcarbonated in the bottle by an unknown infection.

Once the fizz settled enough to pour, all the yeast sediment had been kicked up from the bottom of the bottle and poured out into the glass in huge chunks. Particles hung in suspension in the glass, pale against the dark amber beer, looking thick and jellylike. I tried pouring through sieves, coffee filters, even paper towels; all that did was break the sediment up into tinier particles that made it look like a glass of some odious brown first aid gel.

People drank it, politely, but no one asked for more. I couldn’t blame them. It was nasty looking and didn’t taste like anything. Presumably the infection that caused the gusher fermented the beer too thin, taking out all the body and flavor. But I didn’t give up on it. In the weeks to come, I chilled and drank bottle after bottle, stubbornly rejecting the obvious like some crippled but libidinous salmon struggling upstream towards spawntopia. It never improved.

A few months later, with twelve bottles left, I decided to accept JR 11/27’s fate. But, unable to bring myself to dump the remaining bottles down the drain, I hid them in the back of the Harry Potter closet and forgot about them. Perhaps time really did heal all things, and someday they’d be worth drinking.

This weekend, about a year later, I chilled one and tasted it. I quickly noticed what hadn’t changed.

After two minutes of gushing, I was able to pour the remaining eight ounces into a glass. The color was a deep, dark copper, but chunky with suspended sediment and still very unattractive.

The head dissipated quickly after pouring. The aroma was quite pleasant: tart, cider vinegar and dark fruit (raisin, black cherry, currant) with a hint of Grape Nuts. The vinegar notes suggest that an acetobacter infection was the cause of my gusher. There’s no discernible juniper aroma.

The flavor is better than it was a year ago, but exceedingly dry. It starts out rich and vinous, but quickly fades into a harsh, vinegary zing. If I concentrate after swallowing, I can almost detect an earthy mustiness lingering on my palate. Mouthfeel is practically nonexistent: it’s thin, but not refreshing.

Overall, JR 11/27 has gotten to a point where it’s drinkable, but barely. I certainly won’t serve it to any but my most adventurous friends (and maybe only with a blindfold). But if time hasn’t healed the beer itself, it’s changed my reaction to it. With sour beers being en vogue in craft brewing, this beer with its wild acetobacter isn’t quite the debacle today that it seemed like last year. I won’t reach for it next time I’m thirsty, but I’ll drink another to see how it changes.

I’ll also take a cue from those brewing sour beers, and try blending JR 11/27 with something else. On its own, it’s harsh. But blended with something maltier and more full-bodied, it may bring some complexity to an otherwise boring beer. I can think of a few bottles I have on hand that might benefit from its more “unique” characteristics.

So it seems I’ve learned something that will make me a better brewer, and surprisingly, a better writer. I didn’t get what I wanted out of one of my creations; and yes, that sucks. But with time and an open mind, I reacquainted myself with it on its own terms, and thought of a way to make it work. No one wants to scrap something they’ve created, be it a beer, a book or a batch of brownies. So appreciating one’s creation for what it is – not what it was supposed to be – is a valuable lesson for any creative person.

Of course I’ll do what’s necessary to avoid the unexpected in the future, like being even more careful about sanitation. But when the unexpected occurs, it’s good to remember that something interesting may come out of it – and that there may be something worth saving, even in our disappointments.

A Crescent City Concoction

For a long time now I’ve been in love with milk stouts, and have wanted to brew one. Lisa has also been asking for a coffee stout, specifically one using New Orleans-style coffee and chicory (we’re both New Orleanians by birth), to slake her thirst for java. In a flash of inspiration, I decided to combine the coffee/chicory stout and milk stout into one brew: a “café au lait” stout. You know, just like Café du Monde on Decatur Street would serve if they had a liquor license.

A sweet stout is a great beer style to honor my hometown. Like New Orleans, sweet stout is dark and mysterious, but full of character. It may be intimidating to the uninitiated, even harsh at first; but it’s warm and inviting when you know what to expect. And you discover something new about it with each new taste. That’s all very poetic, I know, but it’s a lot to explain when filling a glass. So adding the ingredients of a real French Market café au lait was exactly what I needed to bring my lofty symbolic interpretation of the city back down to earth.

I named the brew Crescent Moon Café au Lait Stout in honor of New Orleans’ nickname “the Crescent City” and a current obsession I have with all things lunar. I’d like to give a quick toast here to the HomeBrewTalk.com community, and the great people at Austin Homebrew Supply, for helping me finalize the recipe. The grain bill:

- 9 lbs 2-row malt

- 1.5 lb Coffee Malt

- .75 lb Roasted Barley

- .5 lb Crystal 90L

I chose specialty grains with coffee-like flavor profiles to accentuate the coffee in the finished product. I’d never used coffee malt (which despite the name is just barley malt – it has no actual coffee in it) before, but it was advertised as being kilned to 130-170L with a smell and taste like coffee, and it didn’t disappoint. Roasted barley, too, is known for its coffee characteristics, so I opted for it instead of black patent malt to get a little more flavor. The medium-dark crystal malt was added to round out the malt profile of the beer and leave some respectable body.

I started the mash at 153°F, and it dropped to 152°F by the end of the 60-minute mash.

I did two batch sparges and ran 7.75 gallons of 1.032 wort into the kettle. For my last several brews, I have been forced to run off extra wort and boil it down for 90 minutes to hit my target OG. Someday I’ll figure out why that’s the case, but for now I don’t mind the longer boils. It gives me time to catch up on reading and Words With Friends.

I took a sort of bare-minimum approach to the hops, as I really wasn’t interested in a lot of hop character. I want the aroma and bitterness of the coffee and chicory to come through. So I added just .75 oz of 12.4% AA Nugget hop pellets to the boil with 60 minutes left to go, and no late hop additions. I added 1 lb of lactose (the ingredient that makes a milk stout a milk stout) later in the boil, with 20 minutes left.

Notice that I haven’t actually added the coffee and chicory yet. So far, this café au lait stout is just a milk stout begging for a wake-up, but it’s amazing how much it already smells like coffee, thanks to the malts I used. At kegging time, we’ll cold brew between 16-24 oz of coffee and chicory and rack the beer onto that. Cold brewed coffee is recommended because of its smoothness, and it’s really the only way we drink coffee and chicory in this house anyway.

The OG of the wort was 1.064, and I pitched 14 grams of rehydrated Fermentis Safale S-04 yeast. After years of using liquid yeast and rarely using the same strain twice, I’ve recently started using more dry yeast, and this simple English ale strain is rapidly becoming my go-to strain. That’s partly because I’ve been making a lot of British styles, and partly because my busy schedule hasn’t left me with much time to properly prepare liquid yeast for pitching (making a starter, etc.). But I couldn’t have settled down with a finer microbe, because S-04 works fast and flocculates like a rock star, leaving some fruity esters behind but mostly a very clean beer. I brewed this beer on Saturday, and as of yesterday, the kraeusen was already starting to fall.

I’m really excited about this brew. So much so that I couldn’t wait to make it, even though my timing means that I’m going to have a thick, malty stout on tap during the brutal Texas summer. But a friend said to me recently, “Any season is the right season for stout,” and I couldn’t agree more. Especially when my respite from the heat will be a tall, delicious pint of the Big Easy.

So, who’s bringing the beignets?

Philadelphia, and Thoughts on Colonial Brewing

My “day job” (i.e., the one that pays me) sent me to Philadelphia this week. Today I was lucky enough to get a chance to venture out of the cozy suburb where my employer has its offices and into the exciting bustle of one of the oldest cities on the continent. I saw the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall, had a cheesesteak that blew my damn mind, and drove in a circle past the Philadelphia Museum of Art (the famous steps from Rocky).

Philadelphia has had a profound effect on me. The city appears to have been designed with the intent of sending a message to visitors: “Hey, you know that place between Canada and Mexico that the entire world has been watching for centuries? The one with the Bill of Rights and the guns and the Coca-Cola? Yeah, the United States of America. We invented that place, bro.” Everything here is named after George Washington or Benjamin Franklin. The city logo is a bell with a crack in it. The shadiest-looking strip malls have words like independence and liberty in their names. And though it may not be the first thought on the mind of every modern Philadelphian, there is a feeling in the ground itself here that the spot you’re standing on is one where something important happened.

Now I’m back at my hotel, packed and ready to board a plane to return to Austin tomorrow. And because sitting alone in a hotel room drinking Yeungling Lager and listening to the Stone Roses would just be too pathetic, I’ve been inspired by my wanderings today to read about colonial brewing. And thinking it’s high time I do something of the sort.

Summer is around the corner, and a low-alcohol historic colonial brew may be just the thing for backyard refreshment in the Texas heat. And since come May it will be very hard to keep fermentation temperatures down in the swamp cooler in the Harry Potter closet, I can rationalize any esters in the brew as part of the “colonial charm”.

The gravity and bitterness should be similar to that of an English bitter, around 1.040 and 16 IBU. But I’ll get there with 6.5 lbs of American 2-row malt mashed at around 153-154°F. In the boil:

- 1 lb Molasses

- 0.5 oz Northern Brewer (~9% AA) for 60 minutes

- 1 oz Horehound for 5 minutes

I could replace the Northern Brewer with East Kent Goldings, an older and certainly more “English” hop, but that would push the recipe closer to an English bitter than I’d like. Ultimately, I don’t think it matters much because the hops are just for bittering. The flavor and aroma will come from the horehound, which I’m using as a thujone-free substitute for wormwood (an attested colonial ale ingredient). For yeast, White Labs WLP 008 East Coast Ale Yeast is the obvious choice.

Earlier this evening, I read a quote from William Penn himself: “Our Beer was mostly made of Molasses which well boyld, until it makes a very tolerable drink, but note they make Mault, and Mault Drink begins to be common, especially in the Ordinaries and the Houses of the more substantial People.” One can imagine the pride Penn must have felt at explaining to his reader how his city, once a town of molasses-quaffing hooligans, was changing into a place where “substantial” people were starting to prosper enough that they could afford to drink real malt beer. I like to think my brew will be one that Penn would be proud of, and a fitting tribute to how far his city (and the nation conceived here) have come since he landed on the bank of the Delaware in 1682: familiar but changed, refined but true to the spirit of improvisation out of necessity.

The plan is to make this my first brew for May, after this weekend’s New Orleans-inspired café au lait stout (details Saturday!). And if I find myself inspired by any other great American cities, who knows what will be next?

For more on Philadelphia brewing throughout history (including the colonial period) see this article by Rich Wagner from the Spring 1991 issue of Zymurgy.

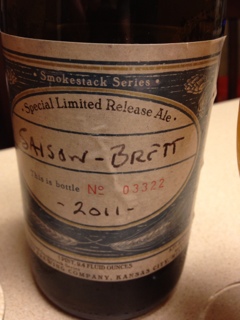

From the Cellar: Boulevard Saison-Brett

The closet under the stairs – affectionately referred to as the Harry Potter closet – is the coolest, darkest part of the house. It’s where I keep all my fermenting beers and where I “cellar” store-bought beers in bombers. I seem to collect them faster than I can drink them, taking them out mainly for special occasions: a Chateau Jiahu on my birthday, a Brooklyn Sorachi Ace to celebrate the purchase of a new Japanese film on Criterion Blu-Ray, that sort of thing. But once in a while, we open one just for the hell of it.

Saturday night was one such time. Thirsty from the effort of arranging our new outdoor furniture into Tetris-style configurations on our limited square of backyard patio, my wife Lisa and I decided to open a bottle of Boulevard Saison-Brett that we’d been eying predatorily for months since we’d bought it.

The words “farmhouse” and “sour” are bandied about so much in the craft brew community lately, it’s easy to forget that just a few short years ago, the word “rustic” was a euphemism for “needs time,” and Brettanomyces (the aggressive wild yeast responsible for the funky flavor in many wild fermentations and notoriously hard to clean out of one’s brewhouse once it’s been introduced) was spoken of in hushed tones like Jack the Ripper was in the back alleys of Whitechapel in the 1880’s. Now many craft beer lovers are on a first name basis with “Brett” and we like a little funk to shake our glasses. But there are no doubt still some brew aficionados out there who haven’t jumped on the funk train just yet. To them I say: this beer’s for you.

The first word that comes to mind when I think of this beer is “accessible”. It’s the same word people use to describe Frank Zappa’s Apostrophe(‘) album, or the Lars von Trier film Melancholia. Boulevard Saison-Brett is as good an entry point for the newbie down the rabbit hole of “sour” beer as those works are into the intimidating corpora of those artists’ careers.

The beer pours a cloudy orange-straw color. The color reminded me of photos from Belgian breweries that I’ve spent hours gazing at online with longing, like a lonely teen with an Internet girlfriend. The head is pure white and rocky, with big bubbles you want to dive right into. There’s a respectable amount of sediment in the bottle, but not too much. To call the aroma “floral” is an understatement. It’s perfumey, with citrus notes and just the tiniest hint of barnyard aromatics from the Brett.

The flavor starts out much the same: perfume on the front end, with a tart and citrusy middle. But this is where it gets interesting. Once the citrus leaves the palate, astringency and sherry-like oxidation notes scrub it right away, leaving the finish very dry. It’s almost like champagne and just as refreshing. There’s not a hint of boozy flavor in this brew, which boasts a not-too-shabby 8.5% ABV.

I paired mine with some crumbled blue cheese, fig spread, and sesame crackers. I had to remind myself to take bites of my snack between sips, as the dry finish left me wanting to wet my whistle again and again.

As for the funk, it was present, but in the background – not the star of the show. Think George Clinton backup singer, not Bootsy Collins standing radiant in all his platform-booted, star-shaped-spectacled glory. There was very little of the barnyard, musty flavor typically associated with Brett beers, but that could very well be because we drank it so soon. Brett character tends to evolve over time, and I just couldn’t wait to try this one; but with a few more months in the cellar, the funky character may have come more to the foreground.

All in all it was a fantastic beer, and I wish I had bought a second bottle to hold onto and see how it ages. Once I get through a few more of the bombers in the Harry Potter closet, I will make sure to save some room for another couple of Saison-Brett bottles if and when Boulevard decides to release another.

Bacillusferatu: the Undead Berliner Weisse

Part of the awesomeness of homebrewing is being able to drink a beer that you can’t buy. If you want to make a chocolate mint stout with a little bit of cardamom in it because it reminds you of your groom’s cake, you can. If you want to make a wheat ale inspired by the 13th-century Italian civil war between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, you can (I might). And if you hear about an obscure beer that people are enjoying in another part of the world, instead of shaking your fist at the heavens and cursing the wretched stars for the circumstances of your birth, you can just make the beer yourself.

In February 2011, I saw a vial of White Labs WLP630 Berliner Weisse Blend at my local homebrew shop. I’d read a lot about Berliner Weisse, a refreshing, low-alcohol sour wheat beer fermented with ale yeast and Lactobacillus bacteria. It sounded delicious, and apparently is available everywhere in Northern Germany, even hot dog carts (frankfurterwagens in the vernacular, I believe) and brothels. But it’s hard to come by on this side of the Atlantic. I was stoked to find the necessary yeast blend – all I needed now were some common malts and hops. “At last! You will be mine!” I shouted, and cackled as I slipped the vial containing the precious mix of microbes into my shopping basket.

Then I got home and started reading about brewing sour beers, which I had never done before. The first rule of Sour Club is you need to be very careful to avoid cross-contamination: that is, you don’t want the bacteria in the sour beer to infect equipment you use to make traditional “clean” beers that ferment with just yeast, because they can turn all your “clean” beers sour. Plastic equipment is very susceptible to cross-contamination, because plastic surfaces get tiny scratches over time that harbor bacteria. I use almost exclusively plastic (I’m clumsy, and would so drop a glass carboy filled with 5 gallons of beer), so for me this basically meant that I needed a whole new set of brewing gear. I panicked. I didn’t have the money to invest in a second set of equipment just to make a beer I wasn’t even sure I’d like. So I stuck the vial in the fridge and forgot about it.

The yeast blend expired in May 2011, but I held onto it for weeks. Weeks became months. Soon it was February, and for all I knew, 99% of the yeast blend was probably dead. It was only then, having become a man with nothing to lose, that I found my courage.

I decided to make a 1-gallon batch of Berliner Weisse, my rationale being:

- A new set of small batch gear was cheaper than a new set of 5-gallon gear.

- If most of the yeast blend was dead, I’d have better luck with a smaller volume of wort.

- I wasn’t sure how much Berliner Weisse I’d need around the house anyway.

I brewed it on March 3. The recipe was based on “Saures Biergesicht” from Jamil Zainasheff and John Palmer’s Brewing Classic Styles, scaled for smaller volume but lower efficiency:

- 1 lb Bohemian Pilsner malt

- .75 lb White Wheat malt

I mashed at 149°F for 90 minutes in a pot on the stove; brew-in-a-bag, no sparge. I added .22 oz of Hallertau Saphir hops (4.2% AA) and boiled for 15 minutes. I transferred 5.5 quarts of wort with a gravity of 1.035 into a 2-gallon bucket I’d outfitted with a stopper and airlock. Then came the moment of truth: pitching the year-old yeast/lacto blend.

On account of the Teutonic heritage of the style and the unholy act of bringing microbes back from the dead, I named the brew “Bacillusferatu” after my second favorite German expressionist horror film (I plan to honor my favorite one soon with a pyment mead of buckwheat honey and Cab Sauv grape juice called “The Cabernet of Doctor Caligari”). But I never had much hope that my creation would live. Surely there was not enough magic left in that vial.

But man, was I wrong. It took a couple of days to get started, but it did. And it fermented wonderfully.

I racked Bacillusferatu into a small carboy 3 weeks later at gravity 1.006. Now it sleeps quietly, the bacteria continuing to ferment the beer and develop its characteristic tartness. In 6 months or so, it should be ready to emerge from its slumber and be unleashed upon the world …

I still have no idea how this beer will turn out. Right now it tastes good and funky, but with no tartness yet. But I have learned two important lessons from brewing it. #1 – As a homebrewer, I alone control my drinking destiny. #2 – Douglas Adams and Charlie Papazian were right. Don’t panic. Relax, don’t worry, have a homebrew. To which I’d add: Never be afraid to try something new.