A Hobbity, Hoppy Midwinter IPA

I’ve written before about keeping it simple in homebrew recipes. Today I’m doing the opposite. I’m sharing a recipe with a lot of bits and pieces, but for a good reason.

Over the course of 2012, I accumulated several open packages of leftover hop pellets. Hops begin degrading as soon as they are opened and exposed to air, and although this degradation can be slowed by storing them frozen in a Ziploc or vacuum-seal bag, that won’t preserve them indefinitely. It’s recommended to use open hops within about 6 months, after which they start to lose their bittering potential day by day as the alpha acids break down.

Of course, it’s not an all-or-nothing deal: it’s not like they’re perfectly okay to use on day 180 and then bad on day 181. As long as they don’t smell funny – like cheese or feet – hops older than 6 months can be used, but the alpha acid degradation (i.e., decreased bitterness) should be taken into consideration for recipe balance and IBU calculation. Fortunately, many brewing programs – like my favorite, BeerSmith – have tools for calculating the effective alpha acid potency of old hops.

So I spent an evening sampling old hops to see how they were holding up, and was surprised to find that the oldest hops in the freezer weren’t the worst ones. For instance, some Saaz and Citra open since 2011 were perfectly fine, but a packet of Warrior from February 2012 was thoroughly becheesed. I separated the good from the cheesy and used BeerSmith to calculate the adjusted AA of the good hops so I could use as many of them as possible in a winter IPA. In homage to new The Hobbit movie coming out this week, I called it Old Took’s Midwinter IPA after Bilbo Baggins’ maternal grandfather, whose memory inspired Bilbo to embrace his adventurous side.

I brewed it on Black Friday in the company of my visiting male family while the ladies were at the outlet mall, which seemed like a great way to show my British brother-in-law (a pub operator who knows a thing or two about a good pint) how we do IPA here in the States.

The grain bill is below. I mashed at 152°F for an hour:

- 12 lbs 2-row malt

- 1.5 lb Munich malt

- 1 lb Victory malt

- 8 oz Crystal 40L

- 8 oz Crystal 60L

- 8 oz Rice Hulls (for efficiency & sparging)

But who am I kidding? The hops are what we’re really interested in here. First up, the oldies but goodies. I’ve noted both the original AA of all the hops below and the adjusted AA, based on BeerSmith’s calculations:

- 0.25 oz Nugget (12.4% orig AA, 11.4% adj AA) for 60 min

- 0.5 oz Saaz (3% orig AA, 1.84% adj AA) for 60 min

- 0.5 oz Falconer’s Flight (11.4% orig AA, 10.4% adj AA) for 45 min

- 0.5 oz Citra (13.6% orig AA, 11.73% adj AA) for 45 min

That was it for the old hops, and I kept them near the beginning of the boil. The reason being that if there were anything unpleasant about them after all this time, it was better to use them early on for bittering, instead of later in the boil when hops contribute more flavor and aroma. Based on my smell/taste tests, it probably would have been fine, but I didn’t want to take the chance.

I also used some fresh hops, mostly (but not all) after the 45-minute mark:

- 0.5 oz Warrior (16% AA) for 60 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 30 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 30 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 15 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 15 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 5 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 5 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) at flameout

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) at flameout

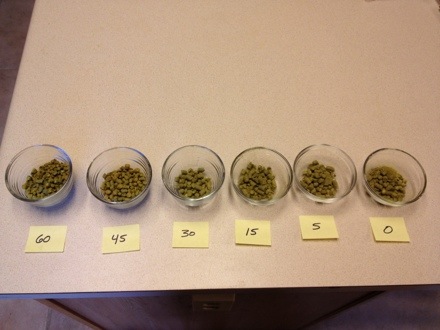

Measured and organized into each addition, all those hops made a pretty picture on my kitchen island:

The OG was 1.070 and I pitched 15.1 grams of rehydrated Safale US-05 yeast. I set the fermentation chamber to an ambient temperature of 63-66°F and it took off like a rocket within about 12 hours. It fermented very actively for about 8 days before settling down, and once I take gravity readings to ensure fermentation is done, I’ll add more Cascade and Willamette dry hops later this week.

If I had any doubts lingering in the back of my mind about using old hops, they were put to rest when I tasted the wort sample I took for my OG reading. It was sweet and biscuity, with a burst of multicolored floral/herbal bitterness, complex and layered as one might expect from so many hops. Tasting how much life was still left in those old hops, I was reminded of the last line spoken by old Bilbo Baggins in Peter Jackson’s film of The Return of the King when, aged and frail but still spirited, he looked out over the sea to the west and said, “I think I’m quite ready for another adventure.”

He who controls the spice …

I had to take a break from blogging last week due to the Thanksgiving holiday here in the United States, during which I played host to my in-laws for several days of family hijinks to the tune of college football, backyard-fire-pit s’mores, an Eddie Murphy retrospective on BET, and lots and lots of imbibed homebrew. I return with many stories I’ll share in the coming days: a rousing adventure of a non-traditional 3-course Thanksgiving beer dinner, and a saga of a Black Friday brew day so bitter it took six bowls to contain all the hop additions.

But first, an update on Colonial Progress Ale. After nearly 4 weeks in the fermenter, it’s just about finished with a gravity of 1.007. That’s a bit more attenuation than I expected, so it will be higher in alcohol, but that may not be a bad thing for a winter session ale.

I’m pleased to report that as the yeast slowly flocculates out, it’s leaving the beer with a much cleaner taste than I was getting from it even a week ago. When I sampled it on Thanksgiving, it was fruity and a little sulfuric. Now it’s clean tasting and very dry, with only a hint of mineral flavor from the molasses and a burst of herbal bitterness from the late spice addition of sweet gale and juniper berries.

What’s missing is any sign of herb or spice in the aroma/flavor arena. So today, a few days before kegging, I made a “spice potion” with the remaining sweet gale and juniper berries.

What’s a spice potion? Despite sounding like something from a Dune or Harry Potter book (or some sick and unnecessary crossover that I would nevertheless read because I friggin’ love both those series: Harry Potter and the Floating Fat Baron? House Elves of Dune? I’m looking at you, J.K. Rowling and Brian Herbert) a spice potion is a method for adding spices or herbs to homebrew without boiling – and thus losing many of the volatile compounds that give those ingredients their distinguishing features – and that’s more elegant than simply throwing them in the fermenter.

It’s simply soaking the herbs/spices in distilled liquor to extract the essence. As I understand it, this works because alcohol is a better solvent than water, so more of the flavor and aroma compounds are extracted than in water steeping, and no heat means the subtler characteristics of the ingredient are retained. And since it’s distilled spirit, it’s safe to add to the beer without fear of infection. Any spirit will do. Vodka is common because of its neutral flavor, but depending on the specific ingredient being extracted, I’ve heard of people using rum, tequila, or whiskey (whose name, incidentally, comes from the Gaelic phrase uisce beatha meaning “water of life”, which is also a solution of pure spice essence in the Dune series – and now we’ve come full geek circle).

I used vodka. And since quality isn’t really important for the small amount that will end up in the beer, I used the cheapest vodka I keep on hand: the stuff that comes in a 1.75-liter bottle for $9, which I use to fill my airlocks (never for drinking). I muddled a quarter ounce of juniper berries with a gram of sweet gale in a mortar and then placed it in a sanitized glass with about 2 ounces of vodka. The resulting mixture wasn’t pretty to look at, but had an herbal/tart aroma pleasantly similar to gin.

I’ll let the potion steep, covered with sanitized foil, from now until Sunday. Then I’ll strain out the chunks, add the essence to the keg, and rack the beer on top of that. Since the bitterness is already prominent in the brew, I think this is the last little flavor kick the beer needs to make it ready for prime time.

Watch this space for the next few days as I share my stories from Thanksgiving week. Since there’s no turkey or shopping involved in either of them, I’m sure you’ll enjoy them despite the passage of time.

Until then, keep the spice – and the beer – flowing.

Unfinished business

With November half over, I'm faced with several unfinished brewing projects and more on the way.

A few days ago, I racked my ginger mead to a carboy for conditioning. Because of my pathological aversion to work which isn't absolutely necessary, I'm a believer in long primaries and won't rack beer to a carboy unless there's a damned good reason (no empty keg available, need the primary vessel for a new beer, cat fur stuck to the inside wall of the bucket, etc.) and I get good beer with up to 6 weeks on the yeast cake.

But for mead, we're talking upwards of 6 months of conditioning, and for that there's no way around racking to a carboy. Not only is it better to get the mead off that autolyzing yeast for the extended aging, but it's essential for clarity: the mead won't clarify until it's removed from the gross lees. It's amazing, in fact, how quickly it does start to clarify as soon as it's racked. Just a few days have passed since I racked it, and it's already several shades darker than it was in the primary due to the yeast flocculating out.

At racking time, the gravity measured 1.001 and the mead had a fruity, floral taste with a little ginger bite but sadly no hint of ginger in the flavor or aroma. My fermentation chamber did its job well keeping the fermentation cool, and it had none of the fusel alcohols my other (uncontrolled temperature) meads had this early on. It might even be ready in less than 6 months, but I have reasons for waiting until April to bottle it. Until then, I'll rack it every 6-8 weeks, add a few Campden tablets occasionally to prevent oxidation, and maybe hit it with some Sparkolloid closer to bottling time. And definitely some more ginger before bottling.

I also took the first gravity sample from the Colonial Progress Ale I brewed 11 days ago. The wort turned out a bit more fermentable than I expected and is currently at 1.009, with an ABV of 4.8% (and the WLP008 yeast, a notoriously slow flocculator, might still be working). It's got a fruity tang I expected from this yeast, and very minimal cidery character from the simple sugar of the molasses. It's really a nice easy-drinking session beer that should be very enjoyable when the yeast settles out. The juniper and sweet gale have largely faded, though. I'll add more spices to the fermenter before kegging. Who knows, I might even rack the beer for the occasion.

The next project on the horizon is an inventory cleaning extravaganza! I've got lots of open hop packets from over the course of the past year that I'll use in a beer to be brewed the day after Thanksgiving. I spent some time tonight rubbing hop pellets between my fingers (while watching Moonshiners on Discovery Channel … now those guys are pros) smelling them and even tasting some of them to make sure they were still hoppy and had none of the telltale cheesiness of bad hops. Fortunately, only a half ounce of Warrior left over from February had any distinctive cheesy notes, so back into the freezer it went to keep on aging until it magically changes from “cheesy” to “aged” and I can use it in a lambic. The other open hops made the cut and will be used next week. More on that recipe soon!

Vote for Progress … hops

Saturday was Learn to Homebrew Day in the USA, and today is Election Day. To honor both events, I did what any patriotic and pedantic zyme lord would. I made beer.

I called it Colonial Progress Ale, and it’s something between an English bitter and an English brown ale. “Colonial” comes from the fermentables, adapted from a recipe I envisioned for a colonial-style ale during a trip to Philadelphia earlier this year. I ended up with:

- 6.5 lbs American 2-row

- 1 lb Victory malt

- 8 oz Flaked wheat

- 8 oz Flaked oats

- 1 lb Molasses

Each of these ingredients was chosen for a reason, starting with American 2-row malt as the base. Wheat is common in colonial ale recipes, including one attributed to Thomas Jefferson. Victory and oats I had no historic precedent for, but I added them for body in the finished beer, along with some bready/biscuity flavor (Victory) and silky smoothness (oats) to accentuate the English-inspired malt profile. I mashed at 153°F for medium fermentability, counting on the highly fermentable molasses to dry the beer out.

Ohhh, molasses. A common ingredient in beer in early colonial Philadelphia (according to a quote from William Penn), I can eat the stuff right out of the jar. But I was nervous about using it after reading John Palmer’s tasting notes ranging from “rumlike” and “sweet” (woohoo!) to “harsh” and “bitter” (ergh). But further research online suggested that harsher flavors were associated with fermenting mineral-rich blackstrap molasses, not the regular unsulphured kind. I went with regular, and added them at the beginning of the boil with high hopes.

The “Progress” part came from the hops: one ounce of 6.6% AA Progress at the 60-minute mark for bittering, and another quarter ounce at 15 minutes for flavor. Progress is a UK varietal related to Fuggle hops, a good choice for English-style ales.

But that wasn’t all I added to the boil. Hops were available to some colonial brewers, but apparently not all that prevalent, so other bittering herbs were common. My original plan was to use horehound, but I realized the medicinal flavor might overpower a low-gravity ale. I thought of rosemary, but was talked out of it by the sages (ha, ha) at Austin Homebrew Supply. I landed on:

- .25 oz Juniper berries (crushed in mortar)

- .5 grams Sweet Gale (dried)

I added the herbs in the last minute of the boil and let them steep during cooling and whirlpool. I may add more later during conditioning.

The wort had an OG of 1.046, a true session ale for the upcoming winter (insert witty apropos Valley Forge reference; I can’t think of one). I pitched the slurry from a 2-liter starter of WLP008 East Coast Ale Yeast – reportedly the Sam Adams house strain – in keeping with the colonial theme. I set the fermentation chamber to an ambient 65-68°F, a little warmer than typical to coax some vintage ester flavor from this low-flocculating yeast.

By this time tomorrow, the future of the United States will be written for the next four years. But regardless of whether my guy wins or not, I’ll have something to look forward to: a beverage in the tradition of the first beers brewed on American soil. Beer has always been a part of American culture, even before there was a United States, and from #1 on down to #44 many presidents have been homebrew aficionados: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were homebrewers and Barack Obama bought a homebrew kit for the White House with his own money. And beer remains one of the few things people can agree on regardless of personal politics.

Don’t forget to vote today, no matter who you’re supporting. Red and blue be damned. We can all party together in the colors of the SRM scale.

The boldness of new beginnings

Foaming with abandon in the Harry Potter closet is a 2-liter Erlenmeyer flask on a stir plate, filled with a starter of White Labs WLP008 East Coast Ale Yeast.

Anyone reading this who has been using liquid yeast without a starter should jump on the starter train. Seriously. It’s as easy as making a tiny unhopped extract brew, because that’s exactly what you’re doing. Just bring 1-2 liters of water to a boil – higher gravity worts will need bigger starters; see YeastCalc for the volume recommended for your batch – add dry malt extract at a rate of 100 grams per liter and some yeast nutrient if you’ve got it. This will make a wort of 1.035-1.040, which is perfect for a starter regardless of the OG of the batch it’s going in. Boil, cool and pitch the yeast. Ferment for 2 days, then cool in the fridge for at least 24 hours before making the “real” wort. Most of the yeast will drop out when chilled, leaving clear (but vile – don’t drink it) “beer” which should be decanted, leaving behind the yeast cake and just enough liquid to swirl up into a slurry. Pitch and watch the magic happen. If you’ve got good sanitation techniques, making a starter carries minimal risk. The rewards are higher pitching rates and better beer. And it’s so easy, there’s no reason not to.

This starter was pitched with yeast that expired in July. I’ve worked with expired yeast before. The yeast/bacteria blend in my Bacillusferatu Berliner Weisse was expired for ten months before I pitched it, though that was into a 1-gallon test batch of a low-gravity wort intended for souring. This starter is going into five gallons of wort for a very different beer: my long-overdue Colonial Progress Ale, from a recipe slightly modified from one I posted in April. Details forthcoming after I brew it this weekend.

As the photo above shows, the expired yeast is spewing so much krauesen I had to wrap it in a paper towel. The expired yeast are healthy as can be, and that’s no surprise. Sure, the expired vial had no more than about 10% of its original population of viable yeast cells, but so what? Yeast cells are dying every day in every carboy, keg and cask in the world, but fermentation continues. Many homebrewers culture yeast from commercial bottle dregs and make great beer with it. Given enough time, even a few sad, dying yeast cells will get their freak on, reproduce and ferment wort. It’s just that the first generations will be weak and languid, and make lots of foul-tasting byproducts doing it.

The purpose of the starter is to make sure those nasty byproducts end up in a beer that’s destined for the drain, not your gullet … while the real wort gets inoculated with a healthy colony of the naturally selected descendants of those few Saccharomycean pioneers who survived the long winter.

So don’t ever be afraid to use expired yeast. Don’t throw it away. You should be making a starter anyway. For fresh yeast, a starter is a leg up. For expired yeast, it’s a new beginning.

Speaking of new beginnings, best of luck to my friends and fellow writers undertaking National Novel Writing Month (“NaNoWriMo”) this November. The goal is to write 50,000 words of a novel in 30 days: fast, raw, unedited. I’ve done it four of the last five years and made it across the 50k mark each time. But I won’t be doing it officially this year. I’ve got too many short stories I want to work on, and a novel already in progress, and I don’t want to distract myself with something new. But I am using November as an excuse to write every day: a blog post, story, novel chapter, anything. I did catch wind of a blog-centric version (“NaBloPoMo”), but I love my readers far too much to subject you all to a bunch of hurried blog posts on whatever random bullshit I can think of to write about.

What do you mean, too late?

Getting Medieval with Ginger Mead

Anyone reading this blog regularly will notice that for the past few months I haven’t really been brewing. I’ve been out of the house a lot, so my homebrew stock hasn’t depleted. Brewing would just net me a backlog of new beer waiting to get stale, not to mention the challenges of brewing outdoors in the Texas summer heat. But now that fall is here, I’ve returned to brewing with a ginger mead from a new recipe. Because ginger is a spice, ginger mead qualifies as a metheglin.

The history/fantasy geek in me loves mead, and it’s hard to find in stores. Most commercial examples are too sweet, better suited to mulling and heating; and my desire to make good easy-drinking mead was a big part of my initial interest in homebrewing. And here’s the big secret: it’s really easy. Meadmaking offers some new challenges for a beer brewer, but the brew day itself is fast and straightforward, especially compared to all-grain brewing. My mead brew day takes 2-3 hours; beer brewing takes me 8 hours from setup to cleanup. There’s no missing mash temperatures. No stuck sparges. No boilovers. No boiling at all – the aroma compounds in honey are volatile and boil off quickly, and honey’s natural antimicrobial properties make sanitizing the must (the pre-fermentation mixture of honey and water) unnecessary.

Preparing a 5-gallon mead must is as simple as heating 2-3 gallons of water on the stovetop, just enough to dissolve the honey (around 110°F), and mixing that with top-off water in the fermenter. I used the 7.5-gallon aluminum pot that usually serves as my hot liquor tank:

Because there’s no boil, I sanitized everything first with Star San, including the pot. Please note that Star San should not be kept in prolonged contact with aluminum, and I only did this knowing I was filling it with water immediately afterwards.I used bottled spring water – for no other reason except that I wanted to pre-chill the top-off water, and Target had it on sale. I’ve made great mead with filtered tap water in the past. I heated 2.5 gallons to 120°F while Lisa peeled and diced fresh ginger root.

Our 4.8 oz of ginger root was only 4.1 oz by the time it was peeled and diced. I added it to the hot water and waited for it to cool to 110°F before adding two different honeys:- 10 lbs Kirkland Signature Clover Honey (Costco store brand)

- 4 lbs Round Rock Honey (local premium wildflower honey)

I racked this to my fermenter and topped it off to 5.25 gallons with refrigerated spring water. The must temperature equalized at about 80°F with an OG of 1.101. I’m targeting 1.005 FG for medium-dry residual sugar and an ABV of roughly 13%.

Meanwhile, I rehydrated 10 grams (2 dry packets) of Lallemand Lalvin K1-V1116 wine yeast in 2/3 cup of cooled boiled water with 12.5 grams Lallemand Go-Ferm rehydration nutrient. Unlike barley malt, honey is very low in nutrients yeast need to thrive, so adding nutrients to the must is … well, a must. I follow the staggered nutrient addition schedule recommended by a user named hightest on the board HomeBrewTalk.com, which calls for 4.5 grams each of diammonium phosphate (DAP) and Lallemand Fermaid-K nutrient at pitching, with additional nutrient additions later during fermentation (there’s tons of great information from this guy here – as invaluable as Ken Schramm’s The Compleat Meadmaker, which I’ve read cover to cover). I mixed the DAP and Fermaid-K into the must with a healthy beating from my drill-mounted aeration whip, pitched the yeast slurry, and shoved it into the fermentation chiller.

All this week, I’ll be aerating the must twice daily with the whip and adding additional yeast nutrients as necessary. Once primary fermentation is complete, I’ll rack to a carboy and age it for at least six months before bottling. I expect to have to add more ginger again for some additional spice after all that aging, which I’ll add directly to the carboy. If it finishes too dry, I’ll stabilize it and add some of the leftover Round Rock Honey.

Meadmaking is extremely rewarding, and a great step outside the box for any brewer. Even extract beer brewers can make mead easily with a minimum of additional equipment, unlike jumping from extract to all-grain beer brewing. And with so few meads available commercially, it’s a great way to share with friends this ancient libation so rich in history, and yet so mysterious to many.

Tapping the All-Galena Pale Ale

Today I kegged the all-Galena hopped American Pale Ale I brewed on the Fourth of July. That’s 7 weeks ago, a long time even by my standards. Due mostly to my day job, I haven’t had friends over nearly enough this summer, so I didn’t have a free tap until now. The Galena APA has been sitting in the primary in the Harry Potter closet all this time.

On the spectrum of anxiety over long rests on the yeast cake, I’m in the middle. I’m not one of those homebrewers who racks off the primary after a week, and I don’t usually secondary at all. But anything longer than 4-5 weeks and I start to get a little antsy. My inner critic kicks in and I begin scolding myself for letting my busy schedule and personal inertia destroy an innocent homebrew by allowing it to age past the terminus of perfection and into the sinister, uncouth dark age of spoilage. Then I get OCD about it. I sniff my hydrometer samples for the telltale “rotting meat” and “shrimp” aromas supposedly typical of autolysis. Once my fears are quelled, I leave it for a few more days, still fearing that the next time I take a sample, it will be too late.

Yes, I could just rack to a carboy after 4 weeks, but that would risk oxidation, which I consider a much more real and terrifying bogeyman than autolysis. I won’t rack unless I intend to age for a long time.

So I’ve been wary for a couple of weeks. But when I took the last sample before kegging, the beer didn’t smell like my Uncle Brian’s backyard during one of his legendary shrimp boils, so that was a good sign. It doesn’t taste like excrement either – huzzah, bullet dodged again.

But more interesting than this tiny conquest over beer-death (hey, I take the victories where I can get ’em) was the result of the dry hopping.

I added a half-ounce of Galena pellets (12.8% AA) a week ago. I always dry hop APAs and IPAs, but especially wanted to do so this time on account of the hop aroma lost during the long rest. Galena isn’t commonly used for aroma or dry hopping from what I can tell, but reports on the Interwebs had me expecting dark fruit aroma from the dry hops.

Those reports weren’t exaggerated. There’s a definite cherry/berry aroma here. It’s deceiving for a pale ale, as it doesn’t exhibit any of the notes we typically associate with “hop-forward” beers: not floral, nor herbal, nor citrusy. But it’s enticing. Coupled with the bready malt notes of the Munich in the mash, the beer ends up smelling a little bit like cherry pie, more so like a tart blackberry cobbler.

That isn’t coming through in the flavor, but I haven’t tasted it properly (i.e., carbonated and chilled) just yet. That first pint will be one for my personal record book, I’m sure. And I’m already thinking about other ways to use Galena as a late-addition hop: as a component in a late-hopped Belgian dubbel, paired with some Special B malt; or in a dry farmhouse wheat with a little bit of rye or mahlab – yeah, I’m still jonesing to use mahlab.

This could be the start of something unorthodox and awesome. You and me, Galena, we’re goin’ places.

My ongoing gas problem

My name is Shawn, and I have a problem with gas.

Specifically, the carbon dioxide tank in my 3-tap homebrew kegerator. About two weeks ago, I noticed that my beers were getting a little overcarbonated. My regulator, it turned out, was set to a very high 14 PSI. I try to keep it at 10 PSI, which produces an acceptable level of carbonation for most beers; not ideal for all, but it’s good enough and a simple round number.

But when my precious beers were suddenly pouring out as 80% head, I knew something was amiss. So I got on my knees, pulled a keg out of the kegerator to get to the 5-pound CO2 tank at its home on the compressor hump, relieved pressure at the tank valve and turned the regulator screw a tiny bit counterclockwise to lower the pressure. It doesn’t take much to get big results: a few degrees of torque on a quarter-inch bolt can result in a difference of 3-4 PSI, and sometimes it takes a day before it stabilizes.

But it seemed like it was going to work, for a few days. Then, by coincidence, the tank ran out of gas (I suspected a leak, but thankfully found none). Unfortunately, it was a Monday and I live too far from Austin Homebrew Supply to go there on a weeknight, so I had to wait 5 days before I could get it refilled. Once done, I happily hooked up the newly filled tank and set the pressure to 8 PSI in the hopes that the pressure differential would bleed out some of the extra carbonation in the beer and equalize at the level I’m looking for.

And bleed it did. I poured a pint of Weiss Blau Weiss a few days later, and it was straight-up flat. The regulator was surprisingly at 3 PSI. I was in full WTF mode by this point, until I realized that I set the pressure before I opened all the valves in my gas manifold. 8 PSI with one valve open to one keg dissipated after I opened the other two valves.

Now I think it’s back to normal. We’ll see in a couple of days. And someday I’ll invest in longer beer lines for the system. Longer beer lines mean more distance for the beer to travel from keg to glass, which means it doesn’t come out so fast and so foamy even when the pressure’s a little high. That’s the next logical step, but I’m hoping to put that project off for a less-busy weekend.

Was there a point to this story? No, mostly I’m just venting. But it’s a solid cautionary tale for any homebrewer out there still slaving over a bottling bucket, manually filling and capping 11 bottles for every gallon of homebrew and thinking, “Once I get my kegging system, all my problems are going to be solved!” I once thought that, too.

Nope. Sorry. There will always be problems. Something can always go wrong. Especially when your hobby’s primary equipment options are mostly Frankensteined together by DIYers from common appliances, picnic gear and plumbing fittings. Problems are a given. You just have to roll with them.

But that’s part of the fun. Anybody can go to the store and buy great beer by the case. What makes homebrewers invest the time and the money in all the constant tinkering? Ingenuity. Creativity. And a morbid, wretched drive to find problems that need solving. It’s the same reason I build my own desktop computers from scratch instead of buying them off the shelf. It’s the same reason I’ve been researching and outlining my novel for an obsessively long eight months, poking holes in my own ideas before I write the first page. Like many men, I may shout and curse and bang my fist when a frustrating problem rears its head, but secretly, I love it when a problem arises, because it’s another chance to prove how smart I am by solving it.

So here’s hoping this problem is solved … for now. A pint is calling my name, so I’ll test it soon. But I’ve got hours to kill before bedtime, and who knows what might be waiting for me in there?

Weizen Up

Sorry, Internet, I've been holding out on you. Weiss Blau Weiss Bavarian Hefeweizen, my experiment in simplicity that I brewed in June, has been pouring for over a week now, and I've had several pints of it already; but I haven't yet written about it. It's high time I did, so you can enjoy it vicariously as much as I've been enjoying it … well … the regular way.

It pours beautifully: a creamy golden color with a gleaming white head. It's cloudy, as a hefeweizen should be, and except for a little bit of floating sediment, it looks as good as any commercially brewed hefeweizen I've ever had. The sediment should clear up once I pour a few more pints off the keg. I did use Irish moss for this brew – as I do for most of my brews – but there are many who choose not to use kettle finings for hefeweizens, and it's possible this worked against me in that it precipitated more particles out to the bottom of the keg. But I'm sure it'll be fine in a few more pours.

The aroma is spectacular. Exactly what I wanted: lots of banana esters, a touch of the sweet, grainy aroma of crisp continental Pilsner malt, and the faintest whiff of clove spiciness. That's about it. No hops on the nose at all. Nothing confusing or muddling. You can tell instantly what ingredient created every single component of the olfactory signature of this beer.

The taste is good, too. It's light, of course, and perfect patio refreshment for my next summer brew session. The yeasty character doesn't lead in the flavor department the way I was hoping it would, not like it leads the aroma. I don't usually bother with that little slice of citrus that most brewheads outside of Bavaria are so fond of in their weizens, but I could see a lemon wedge adding something to this beer, just because it could use a bit more zing (sadly, I don't have any in the house). I don't blame the recipe for this little flaw, rather my fermentation temperature. Next time I make it, I'll ferment a couple of degrees higher for the first couple of days.

The mouthfeel is just right for a summer afternoon: refreshing, not too astringent. It goes down smooth and easy, and at 5.2% ABV is pretty session friendly.

So there you have it. Weiss Blau Weiss Bavarian Hefeweizen was an overall success, not despite its simple recipe but because of it. In fact, it seems to me that my efforts to introduce unnecessary complexity to the process – namely, using kettle finings and overchilling during fermentation – was the main thing that kept it from being (to me) a perfect beer. But that's okay; it's still plenty drinkable, and I'm sure I'll be emptying this keg pretty quickly … no complaints here, because I'd love to make it again. Can I make it even simpler next time? Probably not much so, but the lesson has been hammered home: one doesn't need a mile-long list of ingredients to make a damn good beer.

Of course, the Bavarians have been trying to tell us that for centuries.

A Toast To … Art for Brewing’s Sake

As Central Texas is plagued by thunderstorms, I'm stuck in the house enjoying the last of a bottle of Mikkeller It's Alive! Belgian Wild Ale. And I'm raising my glass virtually to Dustin Sullivan, a fellow member of the online homebrewing forum HomeBrewTalk.com, and the creator of this awesome pictorial on how to make a yeast starter.

I love brewing. I love comic art. And I love anything that's educational in a novel and interesting way. This pictorial is all three, and I'm thrilled to have stumbled onto it. I wish everything in brewing could have been explained to me so simply when I was starting out. Sure, learning as you go is 50% of the fun of brewing (another 25% is drinking the results, and the last 25% is being able to impress your friends by dropping words like “saccharification” and “attenuate” into everyday conversation) … but I'm a knowledge addict, and I'm also pathologically risk averse. So I read everything I could get my hands on when I was starting my homebrew habit, so I'd have a good idea of each step of every process before I jumped in. Sometimes, it was hard to separate the good info from the bad: to separate the clear and “just-enough” from the over-explanatory, and to separate the simple sharing of helpful information from the vomiting of brewlore all over you by guys who just want to impress you with how much they know.

Now, I love John Palmer's How to Brew and Charlie Papazian's The Complete Joy of Homebrewing. They're phenomenal books, and essential for anyone entering the hobby. But if I'd had something as simple and clear as Dustin's yeast starter pictorial for my first extract brew, my first mash, my first rack to secondary, let alone my first yeast starter, I'd have lost a lot less sleep as a newbie.

Dustin also created a yeast calculator website called YeastCalc at yeastcalc.com. It's one of the most comprehensive pitching rate calculators I've seen online for liquid yeast. It tells you not only how big of a starter to make, but also allows you to dial in a target specific gravity for your starter, and tells you how much dry malt extract to use for that target. It even has options for calculating multiple step-up starters, for that 10-gallon barleywine you've been wanting to make. I'll be using this site next time I make a starter, and I recommend you do the same.

So I’d like to raise my beer glass to Dustin Sullivan, another homebrewer out there doing his part to make brewing a little easier and simpler for the rest of us: newbies and veterans alike. Thanks, Dustin. Prosit!

Also, anyone out there who isn't yet a member of HomeBrewTalk.com, check it out. There's heaps of information there. If you have questions, it's a great place to turn; if you have answers, we always welcome new insights. And it's the most helpful, responsive and engaged online community I've ever been a part of. If you join, look me up. My username is shawnbou and I'd love to hear from you.