An homage to UK pubs (and a classic monster movie)

I vote we go back to the Slaughtered Lamb. – Jack Goodman, An American Werewolf in London

Homebrew inspiration can come from strange places. My favorite homebrews are the ones that were inspired not just by an imagined set of flavors, but by places I’ve visited, stories I’ve read, movies I’ve watched, etc. I love using the language of malt, hops, and yeast to tell a story about something more than beer. The trick, though, is that brewing is not an abstract art. A good concept might make for a great conversation starter, but no matter how high-concept a brew is, if it doesn’t taste good I don’t want to be stuck with five gallons of it (I graduated from a Catholic university in New Orleans, but that doesn’t make it a good idea to brew a crawfish & Bananas Foster porter with Trappist ale yeast for the alumni picnic). Finding the right balance between concept and taste is the ultimate goal.

In spring 2011, Lisa and I visited the United Kingdom for three weeks and spent a lot of time in pubs. We drank real ales from so many regional breweries whose names I can’t remember (except for Brains – #1 among zombies in South Wales) served at cellar temperature, often from beer engines – though at one awesome hole-in-the-wall in a one-road hamlet in Scotland I think I remember drinking beer dispensed from a cardboard box. The taste and aroma of real British ale, even the sight of the interior of a British pub, are vivid and powerful memories for me.

In summer 2012, I saw John Landis’ 1981 film An American Werewolf in London for the first time and my nostalgia was kindled by an early scene in the film at a fictitious Yorkshire pub called the “Slaughtered Lamb”. So I brewed a special bitter with English malts and American hops that I named Kessler’s Rampage Special Bitter in homage to the film’s main character and titular werewolf. Not long after I kegged it my sister-in-law and her husband, a native Sussaxon*, came to visit for a week and emptied the keg while I wasn’t looking. I took that as a compliment, and decided to brew it again this summer.

The 2013 version was 94% (8 lbs) Fawcett’s Optic malt, reportedly the base used by Fuller’s and other UK breweries. 4 oz each of Crystal 40 and Crystal 150 rounded out the grain bill. Last year I used Crystal 120 instead of Crystal 150, but otherwise the malt profile was the same in both versions and pretty typical of the style. The mash was one hour at 155°F.

The hops were my chance to freestyle. American homebrewers can be pretty predictable in their hop selections for English pale ales – occasionally someone might get bold and use a little Fuggles, but generally it’s either East Kent Goldings, East Kent Goldings, or another … what’s it called? oh yeah, East Kent Goldings. I suppose that’s what judges look for in competition, but the lack of originality disappoints me. American pale ales and English pale ales are cousin styles, and I see no reason why American hops can’t play a role in a damn fine English bitter if the right ones are chosen – i.e., probably not the 4 C’s (though I suspect someone has done it well).

In 2012, I used exclusively American hops in keeping with the inspiration (you can see both recipes here). For 2013, I deviated with one English hop in the mix:

- 0.5 oz Warrior (15% AA) at 60 minutes

- 0.5 oz Progress (6.6% AA) at 15 minutes

- 0.4 oz Willamette (4% AA) at 5 minutes

Although Progress is English and Willamette is American, both are Fuggle derivatives, so I thought they would pair nicely together despite being a slight variation on the original inspiration. Consider it an homage to Jenny Agutter’s character Alex in the film, the English love interest of the American David Kessler (yes, I can rationalize anything with my artsy symbolic bullshit).

I pitched Safale S-04 into the wort with an OG of 1.046. True to the old adage that “English yeast do it faster,” the fermentation bottomed out at 1.010 less than 48 hours later, leaving me with an ABV of 4.7%, palpable but still sessionable. I kegged it after 4 weeks, and after 2 weeks under refrigeration it’s just starting to get good enough to drink.

I don’t have any of last year’s batch left over to do a true vertical tasting, but I’m a little disappointed in this year’s model. I’m not sure the Progress hops were a good addition (sorry, Jenny). I’ve used them in more robust English-style beers like porters and stouts to great effect, but with so little malt character to hide behind, I’m getting a strong tropical fruit flavor though it is mellowing with time in the keg. The other fault is less diacetyl than I like in this style, though it may be hiding under all those Progress hops and may become more obvious as the hop flavor mellows.

So the beer’s not perfect. But considering I half expected the skies to open up, swarms of locusts and some ancient BJCP curse to fall upon me when I put hops other than East Kent Goldings in a special bitter, I think I’m still coming out ahead. I don’t get the feeling of being an American lost in Britain in this version, but my second Transatlantic ale experiment is good enough to brew again. And again. Until I get it right.

*Sussaxon: a native of East or West Sussex. My brother-in-law assures me this although this term is technically accurate, no one uses it. We both like it because it makes us think of the people of Sussex as mud-splattered, armor-clad Saxons performing great acts of manly savagery like raiding cottages across the southern coast of Great Britain. They’re not.

Baggings! We hates it forever!

My Hobbit-inspired Old Took’s Midwinter IPA is now in the keg. If it seems like that happened really quickly, it’s only because of how late I posted my blog post about the brew day. I fermented it for three weeks before dry hopping it for 6 days. All in all, it was about 4 weeks from mash tun to keg.

I dry hopped it with an ounce each of the same finishing hops I used in the boil, hoping to achieve a nice mix of floral and citrus aroma notes to round out the beer:

- 1 oz Willamette (4% AA)

- 1 oz Cascade (6.2% AA)

It’s been in the keg for less than a day, so it’s too early to know for sure how it’s going to turn out. It tastes good, and it’s got more hop character than it did a week ago. So I think it’s going to be good, but I’m a little concerned that this wasn’t my most successful attempt at dry hopping.

In the past, I’ve dry hopped with pellets either tied in a disposable loose-weave muslin bag, or tossed into the fermenter loose. I prefer loose over bagging if possible for maximum contact, but hop particles in the keg are a problem with more than about a half ounce of hop pellets. With 2 oz of loose pellets, I’d be serving up pints of hop debris for a month.

I didn’t have any muslin bags on hand, nor any time to go to Austin Homebrew Supply to buy any. Searching local retailers for a solution, I came across these spice bags at a kitchen store. They’re for chefs making bouquet garnis, but they are muslin (a tighter weave but still porous), and they are advertised as reusable. The biggest drawback I could see was that they were smaller than the bags I usually use, but since I got 4 in a pack I figured I’d use several.

When bagging dry hops – or when using a tea ball-type infuser, which is also popular – the size of the bag or ball is important. Hops shouldn’t be packed too tightly or else you reduce the surface area in contact with the liquid, which decreases the amount of hop goodness that gets into the beer. After sanitizing the bags with boiling water, I split up my 2 oz of hops into 3 bags along with sanitized marbles for ballast. Two thirds of an ounce per bag seemed to provide lots of breathing room, although I knew the hops would expand a little.

I didn’t count on just how much they would expand.

After I racked the beer into the keg, I found my 3 muslin spice bags at the bottom of the fermenter. The hops had expanded so much the bags looked about to burst, like overstuffed pillows. I didn’t worry about it too much until I was cleaning the bags out, in the hopes of maybe reusing them someday. As I emptied the bags into the kitchen sink, I inhaled deeply, smelling the rich, floral-citrus bouquet coming from the green sludge washing down the drain.

And then it hit me: that’s hop aroma going down the drain. Not in my beer.

The hops expanded so much in those small bags that they ended up packed too tightly. Some of the available hop compounds got into the beer, but not all. So the beer is better than it was, but not as good as it could have been. Should have been. And I’m left feeling disappointed at the waste. A spontaneous decision potentially compromised the end result, and that’s going to bother me until I taste the chilled, carbonated beer and know for sure.

If only I had just used my usual bags! Or something else – anything else!

I should breathe deep and repeat the mantra of Charlie Papazian: Relax. Don’t worry. Have a homebrew. Even if the IPA isn’t perfect, I haven’t ruined it. It’s far from the worst disaster ever to befall a homebrewer, and it’s certainly not the worst thing I’ve faced. Yes, it was avoidable and it’s annoying, but the beer will be fine.

Then from the back of my brain comes a nagging: Is “fine” really good enough?

It’s not beyond repair. I can still add more dry hops to the keg, if needed. And I probably will. But I’ve learned my lesson. I’m sure I’ll find many other uses for these spice bags in the brewery, such as infusing dry herbs that won’t expand. But I don’t think I’ll be bagging dry hops in anything smaller than a nylon stocking in the future.

A Hobbity, Hoppy Midwinter IPA

I’ve written before about keeping it simple in homebrew recipes. Today I’m doing the opposite. I’m sharing a recipe with a lot of bits and pieces, but for a good reason.

Over the course of 2012, I accumulated several open packages of leftover hop pellets. Hops begin degrading as soon as they are opened and exposed to air, and although this degradation can be slowed by storing them frozen in a Ziploc or vacuum-seal bag, that won’t preserve them indefinitely. It’s recommended to use open hops within about 6 months, after which they start to lose their bittering potential day by day as the alpha acids break down.

Of course, it’s not an all-or-nothing deal: it’s not like they’re perfectly okay to use on day 180 and then bad on day 181. As long as they don’t smell funny – like cheese or feet – hops older than 6 months can be used, but the alpha acid degradation (i.e., decreased bitterness) should be taken into consideration for recipe balance and IBU calculation. Fortunately, many brewing programs – like my favorite, BeerSmith – have tools for calculating the effective alpha acid potency of old hops.

So I spent an evening sampling old hops to see how they were holding up, and was surprised to find that the oldest hops in the freezer weren’t the worst ones. For instance, some Saaz and Citra open since 2011 were perfectly fine, but a packet of Warrior from February 2012 was thoroughly becheesed. I separated the good from the cheesy and used BeerSmith to calculate the adjusted AA of the good hops so I could use as many of them as possible in a winter IPA. In homage to new The Hobbit movie coming out this week, I called it Old Took’s Midwinter IPA after Bilbo Baggins’ maternal grandfather, whose memory inspired Bilbo to embrace his adventurous side.

I brewed it on Black Friday in the company of my visiting male family while the ladies were at the outlet mall, which seemed like a great way to show my British brother-in-law (a pub operator who knows a thing or two about a good pint) how we do IPA here in the States.

The grain bill is below. I mashed at 152°F for an hour:

- 12 lbs 2-row malt

- 1.5 lb Munich malt

- 1 lb Victory malt

- 8 oz Crystal 40L

- 8 oz Crystal 60L

- 8 oz Rice Hulls (for efficiency & sparging)

But who am I kidding? The hops are what we’re really interested in here. First up, the oldies but goodies. I’ve noted both the original AA of all the hops below and the adjusted AA, based on BeerSmith’s calculations:

- 0.25 oz Nugget (12.4% orig AA, 11.4% adj AA) for 60 min

- 0.5 oz Saaz (3% orig AA, 1.84% adj AA) for 60 min

- 0.5 oz Falconer’s Flight (11.4% orig AA, 10.4% adj AA) for 45 min

- 0.5 oz Citra (13.6% orig AA, 11.73% adj AA) for 45 min

That was it for the old hops, and I kept them near the beginning of the boil. The reason being that if there were anything unpleasant about them after all this time, it was better to use them early on for bittering, instead of later in the boil when hops contribute more flavor and aroma. Based on my smell/taste tests, it probably would have been fine, but I didn’t want to take the chance.

I also used some fresh hops, mostly (but not all) after the 45-minute mark:

- 0.5 oz Warrior (16% AA) for 60 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 30 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 30 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 15 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 15 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) for 5 min

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) for 5 min

- 0.25 oz Cascade (6.2% AA) at flameout

- 0.25 oz Willamette (4% AA) at flameout

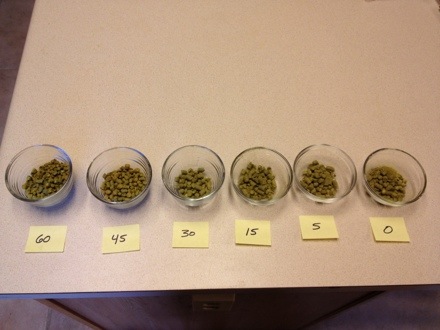

Measured and organized into each addition, all those hops made a pretty picture on my kitchen island:

The OG was 1.070 and I pitched 15.1 grams of rehydrated Safale US-05 yeast. I set the fermentation chamber to an ambient temperature of 63-66°F and it took off like a rocket within about 12 hours. It fermented very actively for about 8 days before settling down, and once I take gravity readings to ensure fermentation is done, I’ll add more Cascade and Willamette dry hops later this week.

If I had any doubts lingering in the back of my mind about using old hops, they were put to rest when I tasted the wort sample I took for my OG reading. It was sweet and biscuity, with a burst of multicolored floral/herbal bitterness, complex and layered as one might expect from so many hops. Tasting how much life was still left in those old hops, I was reminded of the last line spoken by old Bilbo Baggins in Peter Jackson’s film of The Return of the King when, aged and frail but still spirited, he looked out over the sea to the west and said, “I think I’m quite ready for another adventure.”